By Kevan Bundell

[1]

[1]

When it comes to fictional bears in Britain, there are three great allegiances: to Paddington, to Poo and to Rupert. It may be that your family sensibly enjoyed all three. Mine was exclusively devoted to Rupert. This was the doing first of my Great-Uncle George and then of my Mother. On the 3rd November 1930 Great-Uncle George cut out from the Daily Express newspaper part one of a new Rupert adventure ‘Rupert and Bill keep shop’. He did the same each day until the adventure was complete and then gave the cuttings to his niece – my mother. He continued to do the same, almost without interruption, until the 5th February 1937.

I know this because these cuttings are now on my bookshelves. They lived for many years at my Grandma’s, each adventure in a numbered paper bag. I must have gone through them a dozen times during my childhood. When they were passed to me and I came to sort them out I found the bag numbers were quite random and I had to consult the Rupert Museum in Canterbury to discover how to order them chronologically. I then got Mum to slip them into photo albums in an organised fashion. She recalled with pleasure how her Uncle George (with no children of his own) would bring each completed adventure and read them to her – while she looked at the pictures.

My siblings and I were then brought up on Rupert Annuals from the mid 1950s to the mid ‘60s. This means that while Mum was brought up on Rupert in a blue jumper (on the then contemporary book covers) and on stories written and illustrated by Rupert’s creator, Mary Tourtel, we were raised on the red-jumpered, yellow-check trousered Rupert created by Alfred Bestall. He took over the task of continuing the already hugely popular Rupert comic strip in 1935 when Mary Tourtel retired.

Rupert continues his adventures in the Daily Express and in Rupert Annuals even now. New artists took over after Bestall retired in 1965 – but they were all obliged to follow him closely. Since 2010 the paper and the annuals seem to

rely on recycling old stories. Fortunately there is no shortage – and the audience, of course, is renewed constantly.

But why did Rupert become so popular in the first place and why has he remained so popular ever since ?

Rupert is of course a bear. He is not exactly a teddy-bear, but he is close enough. By the time Rupert arrived, the teddy-bear was already a well established part of British childhood – a companion, a comfort at night, a half real, half imaginary friend. At the same time, Rupert is also a child – with a mother, a father and a home. (Rupert even has his own bedroom). He is also, by the way, the ‘baby’ bear of three bears (even if there’s no Goldilocks).[2] Rupert and his family are both (teddy)bears and people. Everything adds up to a character which a young child could and can still identify with.

Rupert also has playmates – friends of his own age: Bill Badger, Algernon Pug, Edward Trunk, Podge the pig and the little girl Margot (all Tourtel creations), Pong Ping, Tiger Lilly, Gregory Guinea-pig, Rastus Mouse (introduced by Bestall) and many more. He also has animal friends – Tourtel’s fox, Beppo the monkey and the ubiquitous black cat – somewhat like the pet a child might have at home – or might hope to have. Rupert is also surrounded by caring grown-ups – not only his parents, but many others : the Professor and his curious dwarf servant, Sailor Sam, the Wise Old Goat, the Nutwood police constable, even Gaffer Jarge. In between, there are the three Girl Guides and Rollo the gypsy boy.

In other words, Rupert lives in a world which is caring, safe and full of friends of all ages – just like his young audience.

Rupert also has rather more secret friends – the Imps of Spring, the merboy, the King of Birds and his entourage, Jack Frost. He also has friends which are really animate toys – the golly and the boy scout for example. These are the kind of friends familiar to most children – in their imaginations. He is even friends with Father Christmas himself ! Rupert also talks to animals and birds – the fox, the wise owl, the hedgehog, a passing sparrow. Interestingly, these various friends are usually known only to Rupert himself, and not to his friends. They are part of Rupert’s own secret, ‘imaginary’ world – just as his young audience might have their own secret, imaginary world known only to themselves, not even shared with friends.

Rupert also has adventures. His adventures range from the scary to the mysterious and on to the enchanting – sometimes all of them within one story. Tourtel’s adventures were often based on the traditionally menacing world of fairy-tales – with witches, ogres and gangs of robbers. In fact she raided a whole range of children’s stories – some scary (pirates, a wolf in a bed, a wicked uncle, a Black Knight, African chiefs and white hunters, Red Indians), some friendly (Robinson Crusoe, Father Christmas), and some simply difficult (Humpty Dumpty). When Bestall took over he was explicitly instructed that there should be no ‘bad characters’. The editor was afraid that the stories were in danger of scaring off their young audience. So was Bestall, but he couldn’t help it. In Rupert and the Travel Machine, for example, one of the earliest Bestall stories (1937) there’s an evil inventor who imprisons Rupert and Bill and will only set them free if they test his new invention. In Rupert and the Pine Ogre (1957) we meet a megalomaniac Lord of Silence who plans to replace all the green woodland of Nutwood with a dark and silent forest of pine. Rupert’s adventures often involve him getting lost in one way or another – in a forest, in a crowd – a familiar child’s anxiety. Or imprisoned – in a castle, in a cave. The fact is, scary makes a good story, and children like to be scared – as long as it all ends safely – as it always does. Both Tourtel’s and Bestall’s stories begin at home – with Rupert off on an errand for his mother, going out to play, or on a day out somewhere. Both end their stories with Rupert safely home again – running to his mother’s arms, recounting his day’s adventures to his incredulous parents.

Nonetheless, Bestall did manage to move Rupert’s adventures away from the dark world of traditionally grim fairy-tale to a world of more delightfully mysterious goings-on and, usually, more friendly, or at least less wicked characters. He also moved from the medieval to more contemporary times – with Rupert visiting London to see the Queen for example, or going on seaside holidays by train. There were always characters still rolling up anachronistically in historical costume though, keeping up the connection to times past and to fairy tales.

Bestall was also told ‘no magic’. But children love magic, as he well knew. He replaced the magic of fairy tales with the magic of Tiger Lilly and her father, the Chinese Conjurer. He introduced the Imps of Spring and of Autumn. They are ‘fairy’ characters but also necessary in a practical way to ensure the proper functioning of the seasons. Still, he managed to replace Tourtel’s magic boots and other magically flying items with more ‘scientific’/mechanical devices such as spring-loaded boots, balloons and propellers. He also introduced the Professor and his various ‘scientific’ inventions and, once, a secret underground travelator which got Rupert back from lost in London to safely home in Nutwood.

Both Tourtel and Bestall were particularly fond of flying – every child’s dream. Tourtel had Rupert flying by magic mostly – although also by aeroplane. Bestall continued the aeroplane and practical theme, but he also had Rupert carried on the back of an eagle, on a winged horse and even on the wind.

Often Rupert’s adventures and the characters he meets are enchanting – the imps, the merboy, talking crabs, even the sea-serpent. And the frogs. Especially the frogs – as Paul McCartney noted.

Rupert’s own character is also an important part of his attractiveness. He is always kind, even when the characters he meets lead him a dance – Raggety the tree-creature, for example. He always tries to do his best to help, even though he is often quite out of control of what’s happening to him – but in the end he succeeds and all ends happily. This is a comforting message to young children who must often feel lost and powerless in their real world.

A key ‘character’ in Rupert’s adventures is the idyllic countryside of Nutwood and its surroundings. Nutwood village sits in a scene of green fields and woodlands. There are hills nearby, sometimes gentle, sometimes rocky and almost mountainous. The landscape is apparently an amalgamation of the Sussex Weald, Surrey, the Cotswolds and Snowdonia (where Bestall had a holiday cottage). Meanwhile, the seaside holidays that Rupert and his family take seem to be to places like the fishing villages and coves of the West country. In any case, Rupert’s local world is an invocation of an ideal English – and Welsh – countryside.

But why should this be of interest to young children ? They would surely be too young to have imbibed the cultural ideal, so it would have no particular draw for them. Unlike their parents. This is the clue of course. Nutwood and its surroundings resonate for adults. So too does the time – the period – in which Rupert’s world is set. Rupert began in the twenties and thirties and when Bestall took over he kept him in that world – which is where he largely remains. For adults Rupert invokes not only the nostalgia of childhood but also a nostalgia of place and time. Meanwhile, young readers become adults and the cultural ideal of the countryside is still absorbed from many sources – including from Rupert presumably.

Adults can also be amused by the puns which Bestall sometimes employs for his story titles – The Mare’s Nest, The Flying Sorcerer, the Blue Moon. Others have pointed out the filmic and dynamic qualities of the illustrations – which work for both children and adults. Ewen Mackenzie-Bowie has shown how the unique combination of rhymes and prose which accompany the stories provide a step ladder for children from being read to by adults through to reading themselves.[3]

But what now ? How long can Rupert survive on the re-cycling of old stories ? Or is that how it best should be ? There is no imperative that Rupert should go on having new adventures forever. His place in cultural history, children’s literature and graphic art is firmly established. And, as noted, a new audience – for whom everything is new – will of course continue to arrive.

*

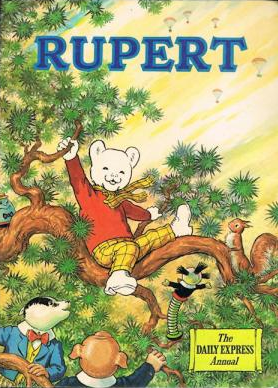

[1] The cover of the 1973 Rupert Annual – the common version. See http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/gloucestershire/hi/people_and_places/arts_and_culture/newsid_8702000/8702628.stm

[2] In fact Tourtel occasionally gave Rupert a younger sister too, which makes four bears.

[3] Rupert – an innovative literary genre, Ewen Mackenzie-Bowie

https://www.icl.ac.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ICL-Journal-3-issue-1.pdf

See also : https://followersofrupertbear.co.uk/