I was in Edinburgh with a day to myself. I thought I would take the opportunity to look for red grouse. They are not hard to find if you are looking in the right place, but you do have to climb to see them. They live only on the higher parts of the British Isles, generally above the tree-line on open heather moors. In my case I also have to travel to see them, as the nearest suitable highlands are some distance away, mostly to the north.

Edinburgh, conveniently, has such highland moors on its doorstep. I only had to take a bus from the city centre to reach the foot of the Pentland Hills, immediately to the south of the city. The Hills are a Regional Park, managed for the purposes of recreation and of wildlife conservation. The sun was shining, though the air was still winter-chilly. A mid-March morning. I carried my picnic in my knapsack and my binoculars round my neck. The paths to the Pentland tops begin at Hillend, where an artificial ski slope has been built. I’d considered whether I might make use of its ski-lifts to ease my ascent, but thought better of it. In fact, it hardly took me fifteen minutes to climb beyond them.I now felt I should be leaving the busy world of the city and its entertainments behind and below. But I was not alone. The hillsides were dotted with other walkers, with joggers, with young and old and middle-aged, all come to take advantage of the sunshine – an infrequent delight in an Edinburgh winter. Among the younger walkers were hardy locals wearing nothing but T-shirts. This is quite usual for Scotland, but very noticeable to a visitor from the south – such as myself, sensibly wrapped in windcheater, hat and scarf.

As I climbed I kept stopping to turn and look at the irresistible view behind me – and to get my breath – often. The whole city lay below. First Blackford Hill and its astronomical observatory, then on to the Castle on its Mound, and to Arthur’s Seat – the remains of ancient volcanoes – with the red cliffs of Salisbury Craggs beneath. The city is a forest of spires, and domes, and blocks and walls of tenement buildings.

Beyond the city, the long waters of the Firth of Forth, and on the far shore, the hills of Fife. Westward I could just see the tops of the Forth (road) Suspension Bridge, and a new bridge being constructed beyond it. The red girder lattice of the magnificent Victorian railway bridge was just visible over the wooded hills. Eastward, the cone of North Berwick Law – another extinct volcano – sat oddly on the surrounding East Lothian plain. Then the Lammemuir Hills to the far West.

I could tell you more. Having lived in the city for a number of years in my twenties, I was familiar with what I surveyed in more detail than I have mentioned. However, the purpose is served if I have prompted you to even the smidgen of a thought that Edinburgh is a place you ought to visit.

It really is.

I kept climbing. From the first top there was a disappointingly long and deep dip and rise to reach the next, and highest. I descended. I noted a group of highland cattle at the bottom of the slope. I noted that one of them stood on the well-worn path ahead. I noted that it was a bull.

I am familiar with cattle – I help a friend look after his beef herd – and I have found that beef bulls are usually perfect gentlemen – or even, sometimes, utter wimps. Dairy bulls, on the other hand, are known to be troublesome. Highland cattle must be like the beef cattle I know, I decided, and in any case, no one would have put a dangerous bull in so public a place. I would keep to the path and ask him to move – or at least pass him with a minimum of detour. Then I noticed that there was in fact an alternative path which went well round the bull. Further to walk, bit of a nuisance, but other people were choosing to go that way.

I went that way.

And so the climb to the topmost peak. As I climbed I heard the call of a grouse behind me. It came from the opposite slope, to the side of the path I had just descended. I turned and scanned the hillside for the bird through my binoculars. But it was too far away to see much and there were no more calls to guide me. I gave up on it and continued my trudge to the peak.

There, I sat and looked westward along the line of the hills, ridges of peaks to the north and south and a valley between. I scanned for grouse. There were none. It was nearly, but not quite, time to have my picnic lunch. I decided to return to the slope where I’d heard the grouse and sit there in the hope of spotting it.

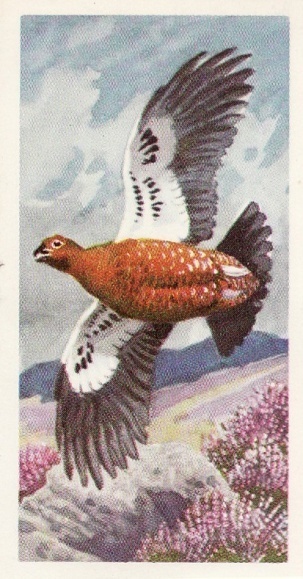

I’d hardly got my sandwiches out of my bag when the grouse called. I found him easily – a cock bird with bright red combs above each eye – about fifty yards off. He scurried from the cover of one bush to another, then peered at me. He flew on rapidly whirring wings before dropping abruptly behind a rock. He was obviously disturbed by my presence, but not enough to stay totally out of sight.

Photo : ?

He had chosen his territory well. The vegetation was quite different from the surrounding slopes. It was a couple of acres in extent and bounded by a stock fence which had kept grazing animals out and allowed heather, bracken, cowberry and mosses to grow, while outside the fence the vegetation had been reduced to tussocks of rough grass. I presume the fencing had been erected for just the purpose of providing a suitable home for red grouse. It seemed to be a second attempt because there was another stock-fenced rectangle within the first, but this one was decrepit and in disrepair and enclosed no more than half an acre – not enough perhaps to have attracted a tenant.

I sat for perhaps half an hour. For the last half of that time I neither saw nor heard anything more of the bird. He had clearly decided I was best avoided. Avoiding human beings is in fact a good idea if you are a red grouse. On this occasion I was apparently the only person showing any interest in them. However, all this changes on the 12th of August each year – when the grouse-shooting season begins. It is known as the glorious twelfth. People with guns come to the highlands of Scotland from across the UK, and indeed the world, to blast them out of the air – and pay very handsomely for the privilege.

Strange glory. Perhaps it’s a spelling mistake.

My friend Dick is a dedicated grouse-slaughterer. He arms himself with one or other of his howitzers and makes the annual pilgrimage to the Scottish grouse moors. He is allowed a brace – that is, two – of the birds he bags and the rest are immediately transported to high class restaurants in London and elsewhere – especially on the 12th itself. In other words, he pays a fortune to provide the estate with birds which they then sell – although, it must be said, not for a half as much as they’ve charged him to shoot them. That is, the money’s in the shooting more than the selling to be eaten. Mind you, if you check what they charge, the restaurants must also make a fine profit on the deal. Dick just loves the sport of it. Grouse fly low and fast and are not easy to bring down. It requires skill. He has it.

I discovered later that grouse shooting also takes place in the Pentlands. This was unexpected. As a Regional Park with conservation as part of its purpose I’d assumed the birds here would be protected. However, the Park is also intended for recreational use. Presumably there’s just too much money to be made from shooting.

Actually, there would not be so many grouse about in Scotland and elsewhere if they were not gloriously slaughtered every year. The moors are managed to encourage their numbers. Controlled burning encourages the growth of young heather shoots – the grouse’s favourite food. This also prevents invasion by tree saplings which would soon alter the nature of the moorland ecology. Management for grouse therefore also maintains a habitat for other moorland species – plants (heathers, crowberries, lichens), birds (dotterel, hen harrier, golden eagle) and animals (hares, red deer, wild cats).

So that’s okay then.

I decided to take a shorter route returning than I had on ascending. I found a half-path through the rough grass and hurried down – disturbing a covey of half a dozen grouse as I did so. They shot off on whirring wings and were gone before I could get a good look at them.

Very sensible really.

Bird Portraits (1957), C.F.Tunnicliffe, Brooke Bond & Co Ltd

thank you for portraying the sport (although i disagree with the word sport) in a fair manner despite not agreeing with it. Most keyboard warriors and their agitators do not understand that without shooting … there sadly would be no moors and no grouse and without the moors, a lot of species will disappear as the so called environmentalists or gree neither pay nor support moor management

Hello Frank,

Thank’s for your comment. I’m wondering what you might prefer to the word ‘sport’ ? I guess there’s an alternative suggestion you could make. Please do !